How Ranitidine Works to Reduce Stomach Acid

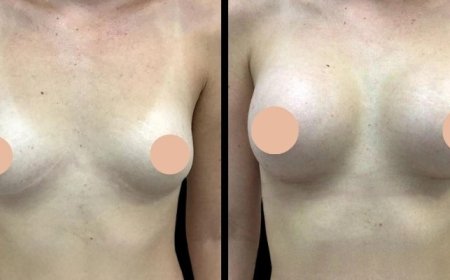

Ranitidine is an H2 blocker that inhibits histamine-induced acid production in the stomach. Histamine is one of the primary signals that tell the stomach to produce acid.

Ranitidine 150 mg, once a commonly prescribed and over-the-counter medication, was widely used to treat conditions related to excess stomach acid, such asacid reflux, heartburn, gastric ulcers, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Known under brand names like Zantac, ranitidine belongs to a class of medications known as H2 (histamine-2) receptor blockers, which help reduce the amount of acid the stomach produces.

This article explores how ranitidine works in the body, its clinical uses, the mechanism behind its acid-reducing effects, and what ultimately led to its withdrawal from many markets due to safety concerns.

Understanding Stomach Acid and Its Role

The stomach plays a vital role in digestion by secreting hydrochloric acid (HCl). This acid helps:

-

Break down food

-

Activate digestive enzymes (like pepsin)

-

Kill harmful bacteria and pathogens

However, excessive acid production or improper acid retention in the stomach can lead to a variety of conditions, such as:

-

Heartburn

-

GERD

-

Peptic ulcers

-

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

Managing acid levels is crucial in preventing discomfort and complications associated with these conditions.

What Is Ranitidine?

Ranitidine is an H2 blocker that inhibits histamine-induced acid production in the stomach. Histamine is one of the primary signals that tell the stomach to produce acid. By blocking histamine at specific receptors in the stomach lining, ranitidine significantly reduces acid secretion, offering relief to patients suffering from acid-related issues.

Originally approved by the FDA in 1983, ranitidine quickly became one of the most popular medications for acid-related problems, available both by prescription and over-the-counter (OTC).

The Science: How Ranitidine Works

Ranitidine works by selectively blocking histamine H2 receptors on the parietal cells of the stomach lining. Here's how the process unfolds:

1. Role of Parietal Cells

Parietal cells are specialized cells in the stomach that produce hydrochloric acid. They respond to three main stimulants:

-

Histamine

-

Acetylcholine

-

Gastrin

Among these, histamine plays a particularly strong role in acid secretion. When histamine binds to the H2 receptors on parietal cells, it stimulates the production of stomach acid.

2. Blocking the Signal

Ranitidine acts as a competitive antagonist at these H2 receptors. It binds to them, blocking histamine from attaching, and therefore inhibits the signal that prompts acid secretion.

3. Result: Reduced Acid Production

With the histamine pathway disrupted, the basal (resting) and stimulated secretion of gastric acid is significantly reduced. This helps lower stomach acidity, offering symptomatic relief and allowing damaged tissues like ulcers to heal.

Conditions Treated with Ranitidine

Ranitidine was widely prescribed or recommended for a range of gastrointestinal disorders, including:

-

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Prevents acid from flowing backward into the esophagus.

-

Heartburn and Acid Indigestion: Alleviates discomfort after meals or when lying down.

-

Peptic Ulcers: Helps heal ulcers in the stomach or upper intestine.

-

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome: A rare condition with excessive acid production due to hormone-secreting tumors.

-

Erosive Esophagitis: Helps reduce inflammation caused by acid reflux.

-

Prevention of Ulcers Caused by NSAIDs or Stress

Onset and Duration of Action

-

Onset: Ranitidine usually begins to work within an hour of ingestion.

-

Peak Effect: Seen within 2 to 3 hours

-

Duration: Effects typically last for 8 to 12 hours, which is why it was often taken twice daily for continuous coverage.

Ranitidine vs. Other Acid Reducers

| Feature | Ranitidine (H2 Blocker) | Omeprazole (PPI) |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of Action | Faster (within 1 hour) | Slower (hours to days) |

| Duration | 812 hours | 24 hours or more |

| Strength of Acid Reduction | Moderate | Strong |

| Common Uses | Occasional heartburn, ulcers | Chronic GERD, ulcers |

While proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole and pantoprazole are stronger acid reducers, ranitidine was favored for faster relief with fewer long-term side effects when used occasionally.

Safety Concerns and Withdrawal

In 2019, ranitidine became the focus of global scrutiny when testing revealed that some formulations contained unsafe levels of NDMA (N-nitrosodimethylamine), a probable human carcinogen. The contamination was believed to result from:

-

Degradation of ranitidine over time

-

Exposure to heat during storage

-

Impurities in manufacturing

As a result:

-

The U.S. FDA requested a voluntary recall in April 2020.

-

Many international health agencies banned or suspended its sale, including in Canada, the EU, and India.

-

Manufacturers pulled products from the market, and production largely ceased.

Alternatives to Ranitidine

Following the withdrawal of ranitidine, several alternatives were recommended:

H2 Blockers:

-

Famotidine (Pepcid) Considered safer and currently the most recommended H2 blocker.

-

Nizatidine Less commonly used, but effective.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs):

-

Omeprazole (Prilosec)

-

Esomeprazole (Nexium)

-

Lansoprazole (Prevacid)

These options are now widely prescribed for both acute and chronic acid-related conditions.

Who Should Not Have Taken Ranitidine?

While generally well-tolerated, ranitidine was not recommended for individuals with:

-

Kidney impairment (dose adjustment needed)

-

Liver disease

-

Allergy to H2 blockers

-

Pregnancy or breastfeeding (only if benefits outweighed risks)

Final Thoughts

Ranitidine once stood as a gold standard for the treatment of acid reflux and related conditions. It offered quick relief, a moderate duration of action, and was effective for both acute and long-term management of gastric acid disorders. Its mechanism of actionblocking histamine H2 receptors in the stomachmade it a reliable choice for millions of people around the globe.

However, concerns about NDMA contamination and the potential cancer risk led to its market withdrawal in many countries, prompting a shift to safer alternatives like famotidine and proton pump inhibitors.

While ranitidine may no longer be widely available, its legacy lives on in the understanding it provided of how targeted acid suppression can vastly improve digestive health. Always consult with your healthcare provider before starting or switching any acid-reducing medication to ensure safety and effectiveness based on your unique needs.